Some things you might not have known:

Nick Soutter knew ABBA lyrics. A lot of them. He sang them aloud with his children in his VW bug convertible with the top down.

He made the best canned liverwurst tacos you ever could taste.

Striding into court in the late 1970’s and early ‘80’s his brown dress socks often hid a secret: painted toenails. In multiple colors. Because he was a single Dad to a little girl who sometimes ran out of fingers and toes to paint.

Three decades later he would sit on the couch in Colorado while his granddaughters divvied up his toes between themselves and applied an extraordinary array of colors. He never removed the polish, and it lasted months.

He was excellent at braiding pigtails. In one tragic incident, he discovered that round hair brushes should never be handed to little girls. The only way to get it out is to cut the bristles or cut the hair. He cut the bristles. One by one.

Probably, it isn’t a complete surprise to you that Nick sometimes howled at the moon — with his kids — off the back steps of the house over the quiet roofs of our Wellesley neighborhood.

We were excellent at sneaking back into our house in silence.

What everyone knows about Nick Soutter is that he was kind. Compassionate, wise, and very funny. He was an adventurer, a talker, and a leader, and a person of extraordinary personal ethics.

To be his kid is more than a privilege; it is a joy. It is an honor, and it will always be a duty. To pass on some part of what he was is work for a lifetime.

He was the son of extraordinary people — here in Boston: his Dad, a war hero and innovator of medical education, and his Mum, the first woman to pilot a sloop solo through the Gulf of Maine.

In Santa Barbara he was parented by his Ma, a philanthropist and great beauty, and his stepdad — whom he called “Uncle Peter” — a descendant of Alexander Hamiliton and JP Morgan, and a war hero in his own right.

Dad’s instant and prodigious love of athletics confused the lot of them.

In Santa Barbara, he arrived at local Little League practice in a chauffeured Bentley, his baseball uniform starched and pressed. He probably wouldn’t have survived long past this arrival if he were not an excellent catcher and ambidextrous hitter. The fact that he was also already gregarious and genuinely interested in people made it possible for him, then, and thereafter, to move in a variety of human circles with great success.

His biggest fan in the Santa Barbara Little League stands was a Spanish-speaking woman who cheered him at every game. He spoke no Spanish at the time, but befriended her, and likely this was the start of his interest in learning how to speak to as many people in as many languages as possible.

In Boston, at Noble and Greenough, Dad played football and ice hockey, both to extraordinary levels of competition.

In his early teens he bought hundreds of record albums to teach himself about classical music. He read The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire for fun. He traveled to Wyoming and worked as a cowhand on a ranch, and then took up skin diving with one of the early Aqualungs. He attended a Russian language intensive at Choate Academy and then traveled to the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War.

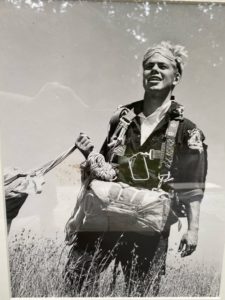

Dad got his pilot’s license while still in high school and went on to take up sport parachuting. He was the founder of the Santa Barbara “Sky Hawks” jump club, and a member of the Cambridge Parachute Club out of Mansfield, Massachusetts.

With three parents holding a variety of degrees from Harvard, the academic expectations for Dad were high — at a time when the definition of academic success was extremely confining, and left little room for people who thought creatively. His teachers at Noble and Greenough despaired of him; he talked ceaselessly, was disorganized, and often inattentive.

Despite it all, he scored very high marks on his Harvard entrance exam and earned a place in the class of 1964.

Around that same time, Dad was awarded a minor league contract with the Santa Barbara Dodgers, and attended Spring Training in Florida.

It was a source of friction, Dad’s preference for athletics over academics; his parents’ insistence that he follow the path they laid out for him.

The matter was decided one summer morning in Santa Barbara. On his way to a parachute jump, Dad was hit head-on by a drunk driver, resulting in the near-amputation of his right leg, and the removal of his kneecap. His days of elite athletics were over.

Although he rarely spoke of this loss, when he did it was always with extraordinary sympathy for the woman who had hit him. He pointed out that he could have just as easily died on the jump that morning, that life is often unfair, and we’re obligated to carry on with what we have.

Carry on he did, arriving at Harvard Yard in the fall of 1959, unable to play football, barely able to walk.

I’ve often marveled at the spirit and heart of this man, that he was not bitter. He loved football, and he was going to participate.

So — tone deaf and utterly without musicality — he joined the Harvard University Band. They made him a member of the “prop crew” — the muscle assigned to protect the band’s 110 year-old drum, “Bertha” from hijinx by rival schools.

Dad served in this role throughout his undergraduate years, through law school, and into the 1980s. He was one of the band’s great and infamous characters, leading cheers, and finding increasingly creative ways to deliver the band to wildly inappropriate settings — a sleeping undergraduate apartment building in the pre-dawn; the Widener Library during study hour; a friend’s wedding. Many, many friends’ weddings.

Through it all, he was guardian and defender of the beloved drum, protecting Bertha from theft and malice by Dartmouth, Princeton, and most ardently, Yale.

In a twist only Nick Soutter could possibly have authored, Bertha was finally successfully stolen in 1984. Two Brown University undergrads dressed as prop crew wormed their way in close to Bertha, loaded her into a Ryder rental truck, and hauled ass south on 128.

Tragically for the Brownies, they were stopped by a Massachusetts State Trooper just short of the Rhode Island line, in possession of a stolen truck and a preposterously valuable antique rawhide drum.

The Brownies perhaps had not considered before embarking on this plan that in the Commonwealth, this meant arrest and arraignment in the Norfolk District Court first thing Monday morning.

Dad had long since stopped his work on the prop crew — so proudly was not at fault in the loss of the drum. He was now an attorney with a solo practice — a multi-lingual litigator… who routinely was at the Norfolk District Court house first thing Monday morning.

Dad was appointed to defend the Brownies.

He represented them without passion or prejudice, and all charges were dropped.

Dad’s years as a litigator were filled with great stories — stories he told brilliantly, with coffee and cigarette in hand, leaving you laughing until your sides hurt.

It is predictable that Dad taught us to be fighters, to never quit, to take calculated risks, to dare greatly. These are easy lessons. Easily executed? No. But telling your child to fight for what she wants is not complicated.

Dad taught me the infinitely harder, more valuable lesson: how to lose. How to admit fault, be accountable, learn… and move on — and that these principles are vital to daring greatly.

I was a teenager when Dad annoyed a federal judge enough to receive a civil sanction — in an amount high enough to get the attention of Massachusetts Lawyers Weekly, who put the story on the front page, November 21, 1988.

Dad told the paper, quote:

“I deserved it. I filed an amended complaint, having been warned by the judge.

I can understand what he did. I don’t agree with it, necessarily. Right now it hurts, but that’s what it’s supposed to do. Whatever else may be true, it’s my fault.”

Being wrong, Dad often told me, is inevitable. Being accountable is a choice.

“Once through and forget it,” Dad would say. Assess your mistakes. Be truthful with yourself. Account to whomever you owe an accounting — and only to them.

And then move on and never let anyone pull you back.

In 1998, Dad left the practice of law and moved to Colorado with his beloved Miss Bubsie, my Moomie, Diane. Together they lived twenty years in the house on Thoroughbred Lane, where Dad taught languages to anyone anywhere in the world who wanted to learn. Grandchildren were born, and brought to the range in Colorado, to hike the Garden of the Gods, bowl and eat fries at Bass Sporting Goods, pose for vintage photos in Manitou Springs — and to relish in their Granddad’s particular brand of humor and affection.

Dad taught me to lose with grace and dignity… but he could never have prepared me for the unspeakable loss of him.

I know that we are obligated to carry on with what we have — and really, what is left to us is astonishing. We have his spirit, his wisdom, his legacy, and his charge to do something great with it all.

This I promise to do.

But losing well is not the same as quitting. He was no quitter, nor am I. As he loved us unwaveringly, so will l love him, miss him, remember him; work to make him proud, and carry him with me, with joy and honor, every day, for the rest of my days.